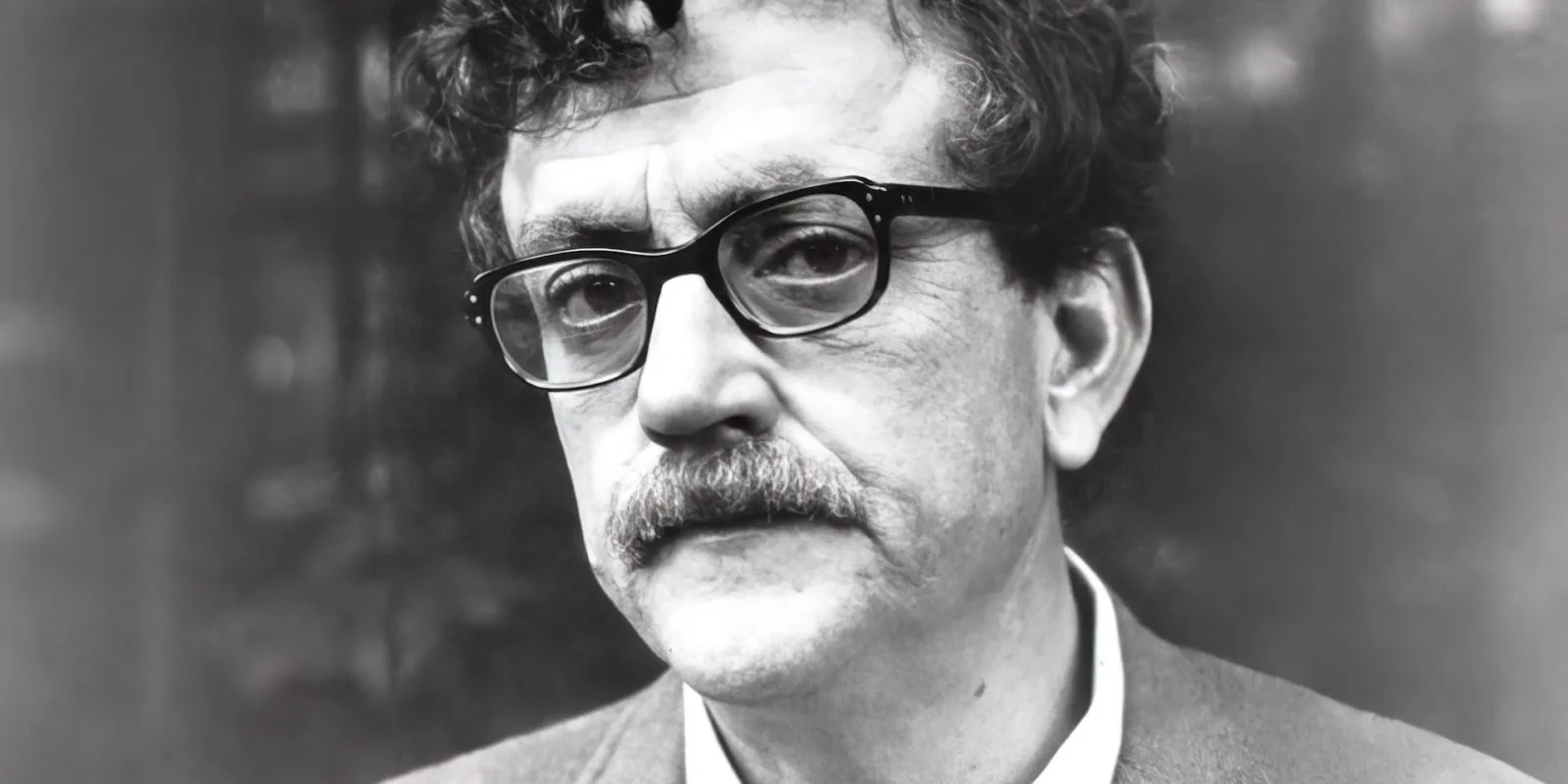

Kurt Vonnegut

“Music does not touch merely the mind and the senses; it engages that ancient and primal presence we call soul. The soul is never fully at home in the social world that we inhabit. It is too large for our contained, managed lives. Indeed, it is surprising that the soul seems to accommodate us and permit us to continue within the fixed and linear identities we have built for ourselves. Perhaps in our times of confusion and forsakenness the soul is asserting itself, endeavouring to draw us aside in order to speak to our hearts. Upheavals in life are often times when the soul has become too smothered; it needs to push through the layers of surface under which it is buried. In essence, the soul is the force of remembrance within us. It reminds us that we are children of the eternal and that our time on earth is meant to be a pilgrimage of growth and creativity. This is what music does. It evokes a world where that ancient beauty can resonate within us again. The eternal echoing of music reclaims us for a while for our true longing.”

― John O'Donohue, Beauty: The Invisible Embrace 2005

From April 2007

“If I should ever die, God forbid, let this be my epitaph: The only proof he needed for the existence of God was music.” Kurt Vonnegut wrote those words in one of his last essays. Email came today from an old friend and it was rather cryptic but it concerned Kurt Vonnegut. I’m living out in Montana and most of my news comes by the United Postal Service in the form of the Chicago Tribune. Ordinarily I wouldn’t know Kurt had died until a week later when my newspapers arrive. Today was one of those ghastly days at work when a person needs a break and checks their email quickly while the boss is in the bathroom, but my boss doesn’t dally in the bathroom, so I don’t have time to read online news.

I replied to my friend who just sent a quote about traveling. I mumbled something in cyberspeak about reading Kurt in college after the fall of Saigon because I had to keep up with the conversations at bars in between sets of my musician friends. I preferred Tom Robbins’ Another Roadside Attraction and Even Cowgirl’s Get the Blues to Vonnegut’s repetitive prose. Somewhere there is a copy of Slaughterhouse Five with tic marks on the inside back cover where a young innocent girl of 20 got frustrated and bored with the “and so it goes” mantra, which now that Vonnegut has died is likened to the repetitive phrasing in the Bible. I told my email friend that I should read Vonnegut again as an adult and so I shall. When in college I only liked Vonnegut’s essays about such tragedies as Biafra and I wonder, now that life has beaten me down and turned me upside down, what it will be like to reread Slaughterhouse Five?

My friend who originally introduced me to Vonnegut was an acoustic guitarist, who grew up to build guitars for the biggest guitar manufacturer in the world and my other friend who sent me the email, is one of the best gypsy guitarists in the world, especially when he is holding a 12-string. My closest friends have always been musicians. Kurt Vonnegut walked Winston Churchill’s black dog of depression frequently and once related in a NPR interview in 2005, “Or what music is, I don’t know. But it helps me so. During the Great Depression in Indianapolis, when I was in high school, I would go to jazz joints and listen to black guys playing, and, man, they could really do it. And I was really teared up. Still the case now.” I am utterly convinced that music saved my life, but not in the way that Vonnegut was speaking.

Most people get squeamish and don’t know what to say when I start talking about thin places and the role the ancient Irish bards played in early Christianity. I believe that some music can create a connection between this world and the other. Art can too, in addition to some poetry, although words are harder to control. When our car was hit at 85 mph, spun round like a pool ball killing my husband instantly, I was listening to my favorite acoustic guitarist. In the ambulance, the Navajo EMT asked if I believed in God. Through the pain of a severe head wound and a back broken in three places, I heard him sing his prayer to reunite my spirit with my body. After spending a Celtic season crisscrossing the country re-driving the roads of my husband’s last hours and our shared life, I discovered first hand, how thin places work. I lived because I wasn’t here when we were hit; I was in between because of the music.

I could say goodbye to my husband when that particular guitarist played a certain song. I never asked for the song, somehow he just knew and it wasn’t the last notes of music my husband heard before he died. During that three month Celtic season, a Presbyterian minister traveled to Iona and prayed the blessing for the soul’s release as the sun set on the beach where my husband wanted to renew our wedding vows. I had said the prayer at the spot along I-90 at the fractioned mile-post marker where Ray died several days before. Along the curving black snake road, this acoustic guitarist was playing in smoky bars and coffee houses. Those beacons of light and music lighted my way as I said goodbye to my husband, whose funeral was held without me the day after my intensive surgery.

I am looking forward to reading Kurt Vonnegut again now through new eyes, curious to find if my life’s experiences will color his words in new shades for me. Vonnegut knew that the proof of God was music and music saved my life.